$18 Million Settlement for Three Men who Spent Decades in Prison For Wrongful Conviction

On May 19th, 1975, Harry Franks, a 58-year-old white man working as a money-order salesman, was shot and killed outside of a convenience store in Cleveland, Ohio. Eddie Vernon, a twelve-year-old at the time, was among the crowd that had gathered around the crime scene by the time the police arrived. He would become the pivotal witness in the ensuing trial, claiming at trial that Rickey Jackson, 18, Ronnie Bridgeman, 17 (who has since changed his name to Kwame Ajamu), and Wiley Bridgeman, 20, were the perpetrators, even though he did not actually witness the crime.

The case against the three men was plagued with issues from its beginning: all three had viable alibis supported by witnesses provided by the defense, Eddie Vernon’s testimony contained problematic inconsistencies and was contradicted by other witnesses, and there was no physical or forensic evidence to link any of the men to the crime. Despite this, all three were convicted and sentenced to death in 1975 (Witness to Innocence). Their sentences were reduced to life in prison in 1978 as the result of a moratorium on the death penalty that was briefly enacted by Ohio (Cleveland.com), and though all three maintained their innocence, the case remained inactive for decades while Ricky, Kwame and Wiley lived out their lives in prison.

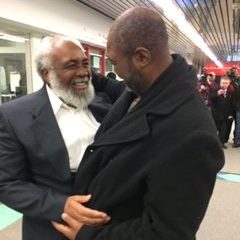

It wasn’t until 2011, when Kwame Ajamu, who had been out on parole since 2003, sought out Terry Gilbert to see what could be done to get his brother Wiley released, that the case began to move forward. Gilbert felt that an investigative journalist would be important to review the case and get media attention, so he contacted Kyle Swenson, a journalist working at the Cleveland Scene. Swenson’s investigation and resulting article underscored the issues in the original trial, and the problems with Eddie Vernon’s pivotal testimony. In the course of his research, Swenson contacted Vernon’s pastor, who would later swear in an affidavit that “Edward Vernon told me that he lied to the police when he said he had witnessed the murder in 1975, and he had put three innocent men in prison for murder. He told me that he tried to back out of the lie at the time of the line-up, but he was only a child and the police told him it was too late to change his story.” (Witness to Innocence). This affidavit, and Eddie Vernon’s subsequent public recantation of his testimony, provided the momentum necessary to finally, more than 35 years after their conviction, begin the exoneration process for Kwame, Rickey and Wiley.

All three men were exonerated in 2014, but it was not until May 6th, 2020, that their civil suit with the city of Cleveland was settled for $18 million. Terry Gilbert (Friedman and Gilbert) an NPAP advisory board member, his partner and NPAP member Jacqueline Greene, and David Mills represented Wiley and Kwame and Elizabeth Wang (Loevy & Loevy) represented Rickey in the civil suit. The case was initially dismissed by the district court at summary judgment, before being appealed to the Sixth Circuit. In speaking about the case and the roughly five-year process from origin to completion, Wang noted the value of the 6th circuit’s opinion, saying: “The 6th circuit wrote a really…exhaustive opinion, which was great not just for this case, but…in its discussion of Monell claims in general. It can be very difficult to prove a Monell claim, and in this case we had some really great evidence that centered on the failure of the city to train its detectives at the time, as well as an express policy that it had…which basically said detectives did not have to disclose exculpatory witness statements to the defense…even today, [there are] departments around the country that don’t have appropriate policies or don’t have any kind of policies at all on Brady evidence.”

Wang and Gilbert went on to discuss the significance of settling a case against the backdrop of a global pandemic. In speaking about their 12 hour settlement conference, Gilbert described how “[the impact of the pandemic] is something that members [of NPAP] are going to be facing in the weeks and months to come…municipal governments [will use], rightfully or not rightfully, the idea that they’re broke or will be broke because of the economy falling apart and the tax revenue not coming in, as an excuse not to pay a settlement that maybe would be greater in a normal world.” He went on to say that while it may be “easy to look at other cases and say, ‘Well, the average amount of damages per year of incarceration is this or that,’ and use those benchmarks as a basis for coming up with numbers…[we all] have to face the reality, particularly when [a city has] no insurance–[of how to get] justice for [the] client.” Though there can be a desire to push for a larger settlement, especially in the context of an injustice as horrific as that endured by Kwame, Rickey and Wiley, Gilbert underscored the need to prioritize the desires of the client above all else. He noted that if the case had gone to trial, even if it wasn’t postponed from its scheduled date as a result of the pandemic, “who knows what would have happened? And if we had prevailed, there would have been appeals, endless motions…[and] it would go on for years, potentially.” Thus, he said, it was pivotal to him and Wang that the clients be “instrumental in formulating the strategy [of the case]”.

Noting that it was not in the best interest of their clients to go to trial, Gilbert mentioned some decisions that were then useful in bringing the defendants to the table to settle. He pointed out the value of both sides first agreeing not to have the conference mediated by the trial judge, as had initially been anticipated through their trial order. He explained that the shared desire for an alternate judge is due in part to the fact that “the trial judge can’t take positions about the weaknesses or the strengths of [either side’s] case, because that judge is going to be trying the case and making decisions in trial.”

Wang went on to elaborate on the impact of the pandemic in their decision making, and recommended considerations that other attorneys might make in their own cases in the midst of COVID-19. She noted that insurance companies have not been impacted by the pandemic to the same degree as municipalities, a reality that makes it easier to push for a larger settlement with an insured municipality, as opposed to one that is self-insured. She also noted the benefits of allowing a city to pay a settlement over time (Kwame, Rickey and Wiley’s settlements will be paid out over the course of the next three years). Such decisions can make municipalities more amenable to larger settlements, because the financial impact is dispersed.

Wang articulated the mixed feelings in a success such as this one at a press conference following the settlement, saying: “What is 39 years of your life worth? Nobody can put a number on that. No amount of money…can compensate them for what they went through.” (Cleveland.com). And yet there is a small relief in the knowledge that these men will at last be able to live their lives as they have always deserved to. In Kwame’s words: “we can control our own destiny now.”